A captive insurance company is a C-Corporation (or a legal entity taxed as a C-Corporation) created for the purpose of writing property and casualty insurance to a relatively small group of insureds. There are additional benefits to creating a captive, but they should be ancillary to the primary purpose of risk management.

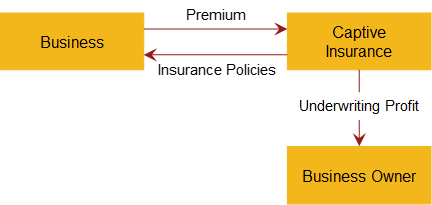

At its most basic level a “pure” captive works like this: A corporation with one or more subsidiaries sets up a captive insurance company as a wholly owned subsidiary. The captive is capitalized and domiciled in a jurisdiction with captive-enabling legislation which allows the captive to operate as a licensed insurer. The parent identifies the risk of its subsidiaries that it wants the captive to underwrite. The captive evaluates the risks, writes policies, sets premium levels and accepts premium payments. The subsidiaries then pay the captive tax-deductible premium payments and the captive, like any insurer, invests the premium payments for future claim payouts.

At its core, a captive insurance company is a risk-financing tool. It places more risk-management control and financial control into the hands of the owner of the captive than exists in a typical commercial insurer-insured relationship. Unlike what occurs in the traditional insurance market, the risks that are underwritten by the captive are precisely the risks that the insured needs underwritten. The policy terms are designed to meet the specific needs of the insured and the rates are based on the specific loss profile/loss experience of the insured—not the average loss rate of the market.

The types of captives designed and managed by Risk Management Advisors are varied. The most common type of captive is the single parent captive. A single parent captive primarily insures risks of the parent company, subsidiaries, and its employees, and may be formed as a subsidiary company. There are two main types of captives that would fit nicely into [Company Name]. Although very similar, the two main types of captives vary on the size of the premium and the taxation of the insurance company itself. The two main structures of captives are:

Captives that are treated as insurance companies are taxed for federal income tax purposes just like any other C-corporation. Thus, these ‘regular’ captives are subject to taxation as a C-corporation at the corporate level on their premium and investment income. All taxable income of a C-corporation receives only ordinary income tax treatment and not capital gains tax treatment. Although regular captives are taxed on their premium income, they can deduct legitimate reserves and other expenses, and may be able to avoid taxation of premium income if they have sufficient deductions. These captives are also called 831(a) captive insurance companies.

Code Section 831(b) permits captives that receive less than $2.3 million of premium income each year to be taxed only on their investment income, and not taxed on premium income. The investment income of 831(b) captives (also known as small or ‘mini’ captives) is taxed at ordinary income tax rates, with no capital gains tax rate available due to their C-corporation status.

These mini captives must elect and qualify for 831(b) treatment each year. Section 831(b) treatment applies only if the total premiums received by the captives are less than $2.3 million in a given year, as opposed to the first $2.3 million of premium received. The fact that the captive does or does not make the 831(b) election does not impact the ability of the parent company to deduct its premiums paid to the captive. Many single parent captives qualify as 831(b) captives, and a parent company (and its related subsidiaries) can potentially create multiple 831(b) captives if the total premiums will exceed $2.3 million.

For a captive to obtain the tax benefits of a captive (e.g. amounts paid to the captive are deductible as insurance premiums), it must be considered an insurance company. The IRS has indicated that a corporation qualifies as an ‘insurance company’ for a particular year if more than half of the corporation’s business during that year consists of activities that, for federal tax purposes, constitute ‘insurance.’ For an arrangement to constitute insurance, two requirements must be met: there must be risk shifting and risk distribution.

The Institute of Risk Management and Insurance (IRMI) offers the following definition of Risk Shifting:

“Used in tax deductibility discussions, the term connotes the transfer of risk to a separate party. In tax disputes, the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) and numerous courts have required the presence of both risk shifting and risk distribution to find a financial arrangement to be ‘insurance’.”

Thus, to qualify as insurance, the risk of loss must be transferred from the entity exposed to the risk to another entity willing to accept the consequence of loss.

The Institute of Risk Management and Insurance (IRMI) offers the following definition of Risk Distribution:

“Used in tax deductibility discussions, the term mandates that enough independent risks of unrelated parties be pooled to invoke the actuarial law of large numbers.”

Meeting the requirements of risk distribution is crucial to qualify as an insurance company not only for tax purposes but particularly to make available the law of large numbers.

The Institute of Risk Management and Insurance (IRMI) offers the following definition of the Law of Large Numbers:

“A statistical axiom that states that the larger the number of exposure units independently exposed to loss, the greater the probability that actual loss experience will equal expected loss experience. In other words, the credibility of data increases with the size of the data pool under consideration.”

The idea is that the larger the pool of insureds (exposure units) exposed to the same types of losses the more predictable those losses become. For example, a trucking firm with 1,000 trucks that has been in business for ten years can more accurately predict the frequency and severity of accidents they will experience annually than a new trucking company in their first year of business with ten trucks. The law of large numbers, crucial to all insurance endeavors, becomes even more important when considering that a captive insurer will be taking on the risks of a smaller number of insureds.

The IRS has issued two ‘safe harbor’ rulings that help define what constitutes sufficient risk distribution:

PATH Act

A few years ago Congress passed legislation regarding the requirements a captive insurance company must meet to be verified as underwriting legitimate insurance for tax and accounting purposes. The Protecting Americans from Tax Hikes Act of 2015 (‘PATH Act’) passed December 18, 2015 and took effect January 1, 2017.

The Basics of the PATH Act

Pre-PATH Act, an insurance company’s premiums could not exceed the $1.2 million, and it had to make a timely election to qualify for section 831(b) tax treatment. After the passing of the PATH Act, the written premium of an 831(b) captive nearly doubled from $1.2 million to $2.2 million. The new law also allowed for the indexing to inflation and an annual basis. As discussed above, the requirements for risk distribution and risk shifting remain.

Where Congress Giveth, They Taketh Away

Although the doubling of the premium was a welcomed development, Congress imposed new diversification requirement.

A captive insurance company must pass one of two tests to satisfy the legislation’s diversification requirement:

There is an exception to the second test for de minimis (2%) amounts of ownership percentage difference. The effect is that the ownership of the captive must reflect the ownership of the insureds, effectively the parent company and subsidiaries, with only 2% variation. Put another way, the heir cannot enjoy an ownership percentage in the captive insurance company that is greater than 2% more of the heir’s ownership in the parent company. This test is designed to eliminate the transfer the wealth of a parent company owned by an original founder to the heir of that original founder by way of a captive insurance company that is substantially owned by the heir.

Notice 2016-66

On November 1, 2016, the Internal Revenue Service (the “IRS”) issued Notice 2016-66 titled: “Transaction of Interest – Section 831(b) Micro-Captive Transactions” (the “Notice”). The Notice identifies certain captive insurance arrangements as transactions of interest and establishes disclosure requirements for those participating in such arrangements or providing material advice to participants.

Transactions of interest are transactions the IRS believes have a potential for tax avoidance or evasion and where the IRS needs more information to reach a conclusion. In this case, the IRS believes that certain, though not all, captive insurance companies making an election under IRC § 831(b) (“831(b)”) may be abusive. The Notice generally describes an increasingly common captive insurance arrangement in which business owners use a captive taking the 831(b) election to cover risks of their businesses and goes on to highlight features sometimes present in those arrangements that may be indicia of abuse.

By identifying these arrangements as transactions of interest, the IRS has imposed disclosure requirements on participants and material advisors. These disclosure requirements come with short-term, hard deadlines and serious potential penalties for non-compliance.

The IRS is focusing on a particular type of 831(b) captive insurance arrangement, which the Notice labels as a “Micro-captive Transaction.” In the Micro-captive Transaction, a business owner or related parties form a captive to insure risks of the business. The captive typically pools its risk with other similar captives. In some cases, the captive issues insurance policies directly to the business and then participates in the pool through a reinsurance and retrocession arrangement.

In other cases, the pool is a fronting insurance company that issues policies directly to the business and reinsures to the participants’ respective captives. Over the last decade, this structure has become a popular means for middle market and privately held businesses to insure commercial deductibles and exclusions as well as high severity, low-frequency risks that had historically been uninsured. This is a valid structure with a bona fide risk management business purpose, and the Notice does note that “parties may use captive insurance companies that make elections under § 831(b) for risk management purposes that do not involve tax avoidance.”

However, in the abusive version of the Micro-captive Transaction targeted by the IRS, certain specific features are evident. The coverages provided by the captive are implausible, inapplicable to the business, vague or illusory or duplicative of the business’ commercial coverage. The premiums paid to the captive are designed to match the business’ desired tax deduction, are not properly underwritten or actuarially determined, are generally inflated and not benchmarked against commercial pricing, not properly allocated to the insureds and not paid according to the insurance contract.

The captive itself is not compliant with applicable insurance regulations, fails to actually or timely issue policies, lacks defined claims administration procedures, and is not asked to cover all applicable losses. Also, the captive is generally under-capitalized, invests in illiquid or speculative assets and makes its funds available to its affiliates through loans or similar transfers that have no tax consequences to the recipient.

The result of these abusive features is a transaction intended to appear as insurance and be treated as insurance, but that is not actually insurance. The true purpose of the abusive Micro-captive Transaction is tax avoidance rather than risk management. The benefit of the transaction is a tax deduction for the business and tax-free premium income for the captive.

To curb such abusive practices, but also recognizing the need for more information to distinguish legitimate Micro-captive Transactions from tax avoidance schemes, the IRS issued the Notice identifying a Micro-captive Transaction with the following features, as well as any substantially similar transactions, as transactions of interest: (1) at least 20% of the captive is owned directly or indirectly by the insured, an owner of the insured, or a related party; and (2) over the preceding five taxable years or the captive’s lifespan, whichever is shorter, either (a) the captive’s loss ratio is less than 70% or (b) the captive provided related party financing in a transaction with no tax consequences to the related party recipient. As a practical matter, the vast majority of 831(b) captives qualify as Micro-captive Transactions under the Notice.

Required Disclosures

The Notice imposes disclosure obligations on participants and material advisors to Micro-captive Transactions. While the obligations can be onerous, they should not be ignored.

Participants

Persons who have participated in a Micro-captive Transaction on or after November 2, 2006 are required to file Form 8886: Reportable Transaction Disclosure Statement (“Form 8886”) subject to certain limitations outlined below. For purposes of the Notice, each of the captive, the captive’s insureds, in some cases the insureds’ owners, and, if applicable, the risk pool is a participant (individually, a “Participant” and collectively, the “Participants”) in a Micro-captive Transaction for each year in which such Participant’s respective annual tax return (or, as applicable, amended return) reflects the tax consequences or tax strategy of a Micro-captive Transaction. With respect to years in which a Participant has already filed its annual tax return, such Participant must file Form 8886 with the Office of Tax Shelter Analysis (“OTSA”) by May 1, 2017.

Notwithstanding the look back to November 2, 2006, the Participant disclosure requirement applies only to open tax years. Generally, the statute of limitations remains open for three years from the date the annual return was filed. However, there are exceptions in which the period for assessment is longer than three years or otherwise extended. Thus, it is important to examine each scenario to determine individual disclosure requirements.

With respect to years in which a Participant has yet to file its annual tax return, such Participant must file a completed Form 8886 as an attachment to its annual tax return. Additionally, each Participant filing a Form 8886 for the first time as it relates to a particular Micro-captive Transaction, must also send a copy of the completed form to the OTSA. However, with respect to a Participant with an annual return due after November 1, 2016 and prior to May 1, 2017, such Participant need not file a Form 8886 with the 2016 annual return; rather, such Participant may instead timely satisfy the disclosure requirement by filing the form with OTSA by May 1, 2017.

Disclosures must identify and describe the Micro-captive Transaction in enough detail for the IRS to understand its tax structure and the identity of all parties involved. Each Participant must describe when and how such Participant learned about the applicable Micro-captive Transaction. In addition, the filing must describe the economic and business purpose of the transaction as well as the expected tax benefits and financial reporting consequences of the transaction. Each Participant must also disclose the name, contact information, and fees paid to each material advisor.

Each Participant that is a captive must disclose: (1) whether, during the preceding five years, its loss ratio was under 70%, it provided related party financing, or it did both; (2) the captive’s domicile; (3) a description of coverages provided; (4) the actuarial basis for the premiums and the name and contact information of any actuary and underwriter who determined such premiums; (5) a description of its claims paid history and an explanation of reserves; and (6) a description of its investment holdings and any involvement of related parties with respect to such holdings. With respect to disclosures (3)-(6), each disclosure must describe the years for which the filing pertains.

In addition to risk shifting and risk distribution requirements, there are other factors that the IRS may consider in determining whether a captive insurance transaction is insurance. These include:

Q: “My lenders require my insurance to come from a rated carrier, how can I issue coverage from my captive and still secure my financing?”

A: For a fee, a rated carrier provides what is known as a “front.” The fronting carrier provides their name for the policy to satisfy the lender’s requirements. The premium and the risk are “ceded” to the captive through a reinsurance agreement.

Q: “If I have a catastrophic claim, can I lose all of the money in the captive?”

A: You decide how much risk you want to retain. Through reinsurance agreements and excess policies, Risk Management Advisors can tailor your insurance company’s exposure to meet your comfort level and objectives.

Q: “Who is else is using captives?”

A: Today there are over 8,000 captives worldwide. Over 40% of major US corporations and many of your smartest competitors have one or more captives. Verizon, UPS, and Centex Homes, as well as many others, use these unique companies.

Q: “Sounds like a lot of work. How much of my company’s resources will I need to allocate?”

A: Risk Management Advisors provides a turnkey program to design, implement and manage your insurance company. This allows you to focus on running your company, while we help you fulfill your objectives for entering the alternative risk transfer market.

Q: “Do I need a Feasibility Study?”

A: Feasibility studies are important because they answer the essential question, “What is my return on investment by using a captive?” Prospective shareholders of the captive should have a clear understanding of what to expect when their capital is used to establish an insurance company.

Once the strategic purpose for a captive has been established, we conduct the feasibility study to determine the payback period and rate of return on capital deployed, and to answer the key organizational and operational questions that have an impact.

Q: “What is contained in the Feasibility Study?”

A: The focus of the study depends on the motivating factors for establishing the captive. In general, the feasibility study is a financial and risk management analysis that always contain the following:

The study later becomes the business plan for the captive with actuarial support for the loss assumptions, a description of how reinsurance functions behind the captive, and how much capital is required to make the captive financially viable.

I’m sure right now you feel like you have been drinking from a fire hose. I tried to take over 20 years of captive knowledge and distill it to a few pages.

Captives are a complex, fascinating, wonderful financial vehicle that for the right client there will be nothing better. For the wrong client, there may be nothing worse. I hope you found this to be a helpful resource as you explore the world of captives.

– Would you agree this has been time well spent so far?

– I can not possibly cover OVER 20 YEARS of content in a webpage

– You CAN create your own insurance company with our help and experience

Subscribe for up to the minute information on captives, IRS memos, rulings, etc. We continually update our subscribers with articles, white papers and case studies they find extremely valuable and useful.

Click below and we will spend 30 minutes discussing your business to see if a captive is a good fit for you or your clients. I guarantee that it will prove to be the most valuable minutes you spend all year.